The drive from Atlanta through to the east coast of Georgia was long. We left far too late, after drinking delicious but overpriced coffee and avocado with poached eggs (who wouldn’t leave late for that option). Driving across the state of Georgia was hot. The weather was humid, the cicadas buzzing even more furiously.

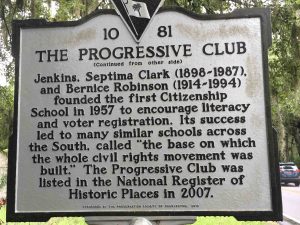

I had been intrigued to learn more about the Gullah people since reading about the work of Septima Clark. The more I learned about Septima Clark, the more I realized how the Civil Rights movement was truly shaped by grassroots organisers – and Septima Clark moved mountains. In fact, she was so crucial to the existence of the movement, that Martin Luther King asked her to accompany him to Norway to receive his Nobel Peace Prize in 1965. As a teacher, she formed the Citizenship Schools responsible for teaching the work of non-violent resistance as well as teaching the local community how to overcome the obstacles such as literacy tests that were structured so that the black community were unable to vote. She set up a school on John’s Island, in a building that is now called the Progressive Club. Septima and her colleagues continued to travel throughout the South, going into communities and recruiting teachers for the citizenship schools.

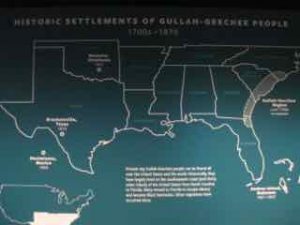

It was on this journey that I learned a vast amount about the lives of the Gullah-Geechee people who have continued to live on Johns Island (and several of the other Sea Islands) in the Lowland area of Georgia and South Carolina.

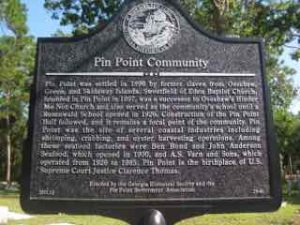

One of the highlights of time in the Sea Islands was visiting the Pin Point Heritage Museum which tells the story of the Pin Point community. The museum is located on the site of the former Oyster and Crab factory, which closed in 1985. The cannery employed dozens of local women in its factory, and many dozens more men as oyster and crab harvesters out in the marsh. Based on donations, the museum opened in 2011. Today, the Pin Point community is comprised of about 300 Gullah-Geechee people about 11 miles south of Savannah in Chatham County.

As we entered the small community, there was a blue sign indicating that Pin Point was the birthplace of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, 1991. As we opened the car door, we were immediately hit with a familiar waft of sea-water, the salt permeating so strongly. I recounted family holidays along this coast, and the warm scent of the salt water was calming, in fact.

The Gullah-Geechee trace their roots to the rice growing area of West Africa. They were brought as captives from Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia to the Atlantic coast – from Florida up to North Carolina allowed to work in the indigo, rice and cotton fields without the plantation owners overseeing them as the weather was too humid. The slaves were more resistant to heat and immune to malaria because of their sickle cell anaemia trait. On the nearby Tybee Island the slave huts still exist.

But in 1865, they stayed so they would own land. The freed slaves were able to purchase property on Georgia’s coast at a reasonable price. But President Andrew Johnson tried to rescind this special order and gave the land back to the Confederate slave owners so the Gullah became sharecroppers. The Pin Point community was founded in the 1896 and became a place to nurture families, live, work and worship as they pleased. They are a maritime people and made a life from the shrimp, oyster and crabs that thrived in the coastal creeks. They built the region and made it an economic and cultural powerhouse. Because they continued to live and work in isolated communities – on coastal plantations – much of their culture, including the language, continues today.

We were welcomed to Pin Point by very capable and knowledgable docents who are Pin Point residents themselves, and who were able to offer personal insights into the once secluded community. Four restored historic buildings make up the museum including the Picking and Cooling House, the Deviled Crab House and the Crab Boiling Pavilion. As a novice to sea-food, I learned a lot about shucking oysters, the numbers of eggs that blue crab lay and all sorts of facts about sea life.

However it was the traditions, language and music that I was drawn to learn more about. I learned that Johnny Mercer (from nearby Savannah) was inspired by the gospel singing that the women sang as they worked shucking oysters and based his lyrics to the song “Moon River” on this community. Mercer’s exposure to black music was perhaps unique among the white songwriters of his generation. As a child, Mercer had African-American playmates and servants, and he listened to the fishermen and vendors about him, who spoke and sang in Geechee.

I learned about the “Seeking (coming of age)” ceremony that happened to boys when they were 12 or 13. For 3 months, every night they had to get up at midnight and go to the woods to pray. If they were caught looking back as they walked their faith in Christ would be doubted and they couldn’t be baptized. For 30 nights their dreams would be interpreted by one of the elders and finally they would be baptized down by the beach, on the shores of the marshes at low tide.

Their adoring nicknames for each other were highlighted in the comprehensive video. It is the creole mix of languages that include vocabulary such as “chirrin” meaning children, and “coota” meaning turtle. Religion defines the Pin Point community and the “the Sweet Field of Eden” Baptist church is a main focus of community organization. The values of the church permeate as discipline and etiquette are taught to the young children who are threatened with a beating if they challenge authority.

There are other Gullah-Geechee communities on the Sea Islands, especially the Penn Center that we didn’t make it to as it was closed by the time we finished the long drive across Georgia. However, the relationship between Clarence Thomas and Pin Point begged many questions for us and triggered us to conduct further reading that shone Thomas in a questionable light. Here is a New York Times piece that we read that begins to address what I mean: https://mobile.nytimes.com/2011/06/19/us/politics/19thomas.html

Once again my head was buzzing with thoughts. How can these small communities survive when modern living threatens them? Did these types of communities avoid the lynchings and other methods of terror during Jim Crow?

I urge you, if you are ever in that part of the world, to drive through the Sea Islands and visit Pin Point for yourselves. It was certainly an afternoon of discovery. Septima Clark would have to wait for another day.