Today I drove from Birmingham, Alabama to Atlanta, Georgia by myself.

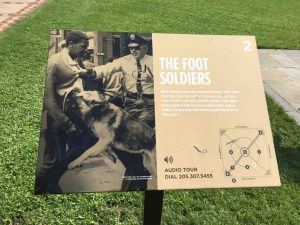

As I drove, I listened to Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History podcast about the Civil Rights movement, and one in particular called The Foot-soldier of Birmingham. It was such a pleasure to listen to someone comment on a place of historical significance that I had just spent the day visiting. This particular place was Kelly Ingram Park.

If you haven’t yet had the chance to listen to the podcast, here is the link: http://revisionisthistory.com/episodes/14-the-foot-soldier-of-birmingham

It uncovers the history of the famous statue in Kelly Ingram Park, which clearly evokes the unbelievable violence of police and other state authorities on to the non-violent African-American community. But if you listen, you will realise the statue has a different history than what meets the eye.

Kelly Ingram Park was the gathering place for peaceful protests in the 1960s and is the gathering place for peaceful reflections today as a well as gathering for a considerable number of homeless people begging for money. The Park is just across the street from the 16th Street Baptist church as well as the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

Before I explain a bit about the history of Birmingham, I wanted to describe a most serendipitous moment. When I first entered the Civil Rights museum, I took notes on everything I saw, including the film at the beginning of the exhibit. As the film ended, a woman approached me and asked me if I was a teacher! “Indeed, I am, are you?” I asked Merle is also a teacher and she began her Civil Rights journey in Washington DC and will finish in Memphis. We soon learned that we are doing the exact same trip – just backwards from each other. It was so fortuitous for us to meet exactly half way, and we shared tips and information. This is Merle and I in the exhibit. Merle – if you are reading this, I hope you stay safe on your travels.

I learned that Birmingham was founded in 1871, during the post-Civil War Reconstruction period. It was named for my parents home-town of Birmingham, England, for its industrial strength. It developed as an industrial and railroad transportation center, based on mining, the new iron and steel industry, and railroading. The city was developed as a place where cheap, non-unionized, and African-American labour from rural Alabama could be employed in the city’s steel mills and blast furnaces, giving it a competitive advantage over unionized industrial cities in the Midwest and Northeast.

From its founding through to the end of the 1960s, Birmingham was a primary industrial center of the southern United States. Its growth from 1881 through 1920 earned its nickname as The Magic City. The white community owned the industrial businesses and the black community worked the rails fueling the city’s progress with backbreaking labour. Birmingham became a proven success and the Magic City prospered with the smell of sulfur.

Although African-American workers played a key role in establishing unions during Reconstruction, the Birmingham KKK chapter was the largest in the country and the power of the Klansmen undermined any lasting interracial unity. The city laws also mandated segregation.

I learned that the 92% of the white community of today (including the Jewish community) live in a beautiful suburb called Meadowbrook. It was on one side of the mountain, where the iron-ore was mined. The white community currently makes up 13% of the greater Birmingham population. The remaining 87% of the community is African American and lives in the more central Birmingham area.

From my brief time there, I can’t say that I picked up on an overt racism, per se. I did see white policeman on Kelly Ingram Park making it clear to the African American homeless people that pan handling tourists was not allowed and if pursued they would be directed elsewhere. But what I did understand from speaking to people at breakfast, the security guards at the museum, the members at the synagogue, the people at the Bourbon tasting, was that there was an evasion to address the underlying feeling and reality. No one wanted to take responsibility for moving forward, as nobody has a solution to continued racial division and ultimately they feel like its getting worse. People focus on enjoying their own lives, building their own communities, and ensuring that their loved ones are cared for. The shul’s community is an example of this.

Racial separateness – American apartheid – was deeply ingrained in every aspect of city life. In downtown Birmingham, even the parking lots were segregated! Violation of Birmingham’s segregation laws was punishable with a $100 fine or six months in jail.

It’s the vicious use of violence that continues to scare me. Joanne had showed me the display in Selma of the nightsticks and Taser-type sticks used to beat people. And official violence by the Birmingham city authorities was no different. Private violence by those same “authorities” was used regularly to enforce segregation. Days after the Montgomery Bus Boycott ended in 1955, singer Nat King Cole was attacked and beaten by whites while performing on the stage of Birmingham’s municipal auditorium because, his attackers said, he was singing love songs to white women. And because of the 1954 Brown Supreme Court decision as well as the success of the Montgomery boycott, Birmingham became knows as Bombingham, as numerous bombings occurred. The rabbi told me that 54 sticks of dynamite were found next to the shul before they were ignited. Nowhere was safe.

Such savage white conduct fueled intensifying efforts to bring about change. The most fearless President of the Birmingham NAACP was Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. He was a man whose courage and determination make me feel so small in my actions. He brought together ministers, and packed mass meetings in all the churches across the city. He formed the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights set up to deliberately break segregation laws. Even though Shuttleworth’s house was bombed and completely destroyed on Christmas Eve, he pushed on and led protests, marches, and even attempted to register two if his children at his local white High School. He was beaten by a white mob with brass knuckles and chains. As I type this, I feel sick thinking about brass knuckles. Imagine the pain. Imagine the determination to feel that if you keep going you could make change, but forever wondering if you really could succeed. I wonder if he ever wanted to just give up.

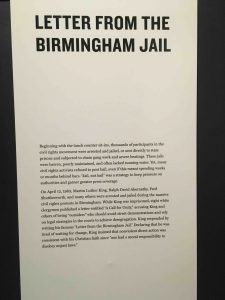

So by the time Freedom Riders arrived in Birmingham in 1961 many people had been jailed and bailed out. 18 black homes, churches and 1 synagogue had been bombed. Shuttlesworth invites MLK to come to Birmingham, and they begin to plan Project C – for Confrontation. They campaigned with sit-ins at lunch counters across the city. And they were arrested. Police Commissioner Bull Connor, the racist of them all, then arrested King for marching on Good Friday. He penned his Letter from a Birmingham Jail whilst in solitary confinement. After 8 days he came out and agreed to the controversial strategy of using children in protest marches.

Kelly Ingram Park is filled with statues of children. First of all it commemorated the 4 little girls who were killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist church.

Secondly, it was children who marched as part of the Children’s Crusade in the spring of 1963. They poured out of the 16th Street Baptist Church, and some 500 were arrested. Ay after day, children and students continued to march, even when they were met with snarling German shepherd dogs, and powerful blasts of water from firehouses. Policemen attacked as hundreds of white lined the sidewalks cheering and urging brutal police action.

Despite the Southern hospitality (which I received readily), I was really ready to leave Birmingham and head east to Atlanta. I was tired after a week of intense thinking about racial tensions. I was looking forward to seeing good friends and celebrating Shabbat. I kept thinking if I was tired, how tired would Fred Shuttlesworth be. I recalled the grave of Fannie Lou Hamer were it was written: “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.” I guess I wasn’t that tired, after all.