It’s nearly impossible to be in Atlanta and not feel the ghosts of the civil rights movement — and for good reason. Atlanta is the home of the movement and many of the key events were either planned or held here. The city is where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. preached at Ebenezer Baptist Church and where the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) calls home. It is where African-American leaders met with white Atlanta business and civic leaders to dream about and help create a new integrated world.

There was something about Atlanta that was more familiar than any other southern city that I had visited thus far. It could be because it was a larger urban center where I have dear friends (and therefore it was welcoming and comfortable) or because it felt like Atlanta’s nickname “the city too busy to hate,” was palpable.

But it was more than that. It differed from other Southern cities in important ways. Since the early 20th century, the “Atlanta style” of managing race relations had white and black leaders meeting behind the scenes to decide what was in the best interest of community. The Center for Civil and Human Rights (which I will mention in a bit) asserts that Atlanta was a special case in the South for its tolerance. In part, that was because of the strength of black institutions including King’s alma mater, Morehouse College and one of the earliest and most influential black newspapers, the Atlanta Daily World.

Dr. King was born on Auburn Avenue, into Jim Crow laws like this Georgia statute: “The marriage of a white person with a Negro or Mulatto or a person who shall have one eighth or more of Negro blood, shall be unlawful and void.” Or this one: “It shall be unlawful for any amateur White baseball team to play baseball on any vacant lot within two blocks of a playground devoted to the Negro race.” That doesn’t feel too tolerant to me. The claim that Atlanta was a city “too busy to hate” is one which might be true in some cases – but does not absolve it either.

One of the things this trip has taught me thus far is that one cannot see everything, go everywhere and do everything. One must choose how to spend one’s time – quality over quantity. And so upon arrival in Atlanta, I chose to spend my afternoon at the new Center for Civil and Human Rights. The main exhibition recalls those Jim Crow laws but what was interesting is where the museum has been placed. It is not located on Auburn Avenue, where King is buried, or near the house where he grew up. It has been built alongside the main tourist attractions of Atlanta’s downtown on land donated by the Coca-Cola Company, which runs the nearby World of Coca-Cola museum. Across a plaza is the immense Georgia Aquarium which has become an international destination. And across the park is the Inside CNN studio tour. Perhaps the new location suggests that the conversation about Civil Rights is just as important as entertainment and large corporations. Perhaps it suggests that this reality is as much part of the 21st century than in the 60s.

Outside the new Center for Civil and Human rights stands a monument called “Passage,” which includes a water feature. The sculpture is engraved with quotes from Nelson Mandela and Margaret Mead. The water rolling down evokes King’s use of a Biblical phrase that justice will “roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

The main source of the center’s appeal, though, lies in its main first floor exhibition, “Rolls Down Like Water: The American Civil Rights Movement,” which follows the doctrines of a museum of experience rather than a museum of objects.

You begin by passing through a corridor whose two sides are labeled in neon like the signs of the Jim Crow era, showing the “White” and “Colored” worlds of Atlanta in the 1950s — separate and unequal (including segregated baseball teams, the Atlanta Crackers and the Black Crackers).

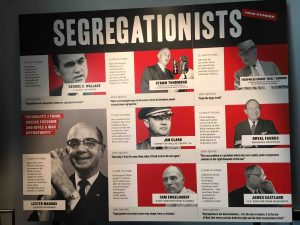

A wall devoted to portraits of segregationists chillingly cites beliefs once proudly proclaimed. (“There’s not enough troops in the Army to force the Southern people to break down segregation.” — Strom Thurmond.)

A display of Jim Crow laws, with panels that change like railroad timetables, outline the onetime laws of each Southern state. (Florida: “The county superintendent shall store separately the books which have been used in White and Negro schools.”)

The main interactive is a mock lunch counter on which you sit like the protesters of the late 1950s, wearing headphones that evoke the tumult they faced: taunts, knocks (physically felt from vibrating stools), insults — temptations to give up on nonviolent protest. It was unbelievably real. I sat there with my eyes closed and became really scared. I couldn’t last the whole 3 minutes of the recording. Courage. Training. Practice. I was in continuous admiration for the persistence, the organization and the courage of the Civil Rights foot-soldiers.

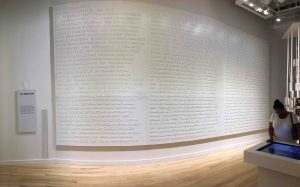

The exhibition itself is finely executed. It ends with a display of martyrs to the movement, some well known, others more obscure: Lamar Smith in Brookhaven, Miss., shot dead in 1955 on the courthouse lawn by a white man — no witnesses would testify, no convictions; Clarence Triggs a bricklayer who had attended a civil rights meeting in Bogalusa, La., found dead in 1966 on a roadside, shot through the head; after protests two men charged with the crime; both acquitted. There were so many, and it felt like the hall at Yad Vashem – the tower of memory.

But this martyrology, which is accompanied by a wall listing the civil rights legislation of recent decades, is presented as a kind of closure. It even inspires a form of exhilaration about how much was accomplished in what is, in the scheme of human injustice, a very short time.

It begged many questions as to what happened after 1968? Did the United States go through its own Reconstruction, a time of building and chance for equal opportunity – only now to be thrown back into what looks like a third Civil War? Civil rights are being threatened this morning as Trump announces that Transgender people are not allowed to join the military.

America is the home of the brave, but what about the land of the free?

It feels all too familiar.

Dr King and Coretta Scott-King are buried in the King Center for Non-Violence. Their graves are surrounded by water, accompanied by an eternal flame.

Across the street is the International Civil Rights Walk of Fame created to give recognition to those who sacrificed and struggled to make equality a reality for all. There is a parade of embedded 2’x 2′ granite markers featuring the actual footstep impressions of civil and human rights icons, such as Rosa Parks, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, Ambassador Andrew Young, US Congressman John Lewis, and others. The walk highlights men and women, black and white, who were “brave warriors of justice.” In addition, the inductees include Tony Bennett, Sammy Davis Jr., Herman J. Russell, Ralph McGill, Thurgood Marshall, Evelyn Lowery and Marian Wright Edelman.

Incredibly hot, and after an intense afternoon, Shabbat beckoned. We were kindly welcomed for supper by Deborah Lipstadt and her community who live in Congressman John Lewis’ district.

We enjoyed warm conversation, delicious food, melodies, and a midnight swim. I appreciated listening to conversations about Jewish communities, as one would in any community: politics, singing, rabbis – and especially the old adage of: “where did you buy your challah?” But I brought up visiting Bryan Stevenson’s EJI office and told them about the Lynching Memorial. They were intrigued. None of them had visited Mississippi before. They were curious and wanted to know more. It made me realize how much Bob Moses’ statement rang true: “when you’re in Mississippi, the rest of American doesn’t seem real. And when you’re in the rest of America, Mississippi doesn’t seem real.”